THE EXISTENTIAL TRINITY

By Michael Tsarion

…both Jung and Heidegger regard that process of differentiation as essential to human fulfilment – individuation for Jung, and authenticity for Heidegger – Roger Brooke

Have you ever wondered why you can’t find what you’re looking for in life? Have you ever been dismayed that after a long search you’re still not there? Why is knowledge so damn elusive? Why is mastery so difficult? Why despair, loss, futility, failure, resentment and death? Why one short life and so much to learn and gain?

The philosophy of Existentialism supposedly addresses questions of this sort. It’s said to be preoccupied with themes of loneliness, alienation, disenchantment, crises and breakdown. Why is the Age of Affluence also the Age of Anxiety? Why so many suicides among the privileged and smart? What’s wrong with society? Is civilization a good idea or is it terminal? What is a person’s responsibility toward themselves? Are the terms “individual,” “independence” and “uniqueness” ultimately meaningless? Am I wrong to go along to get along?

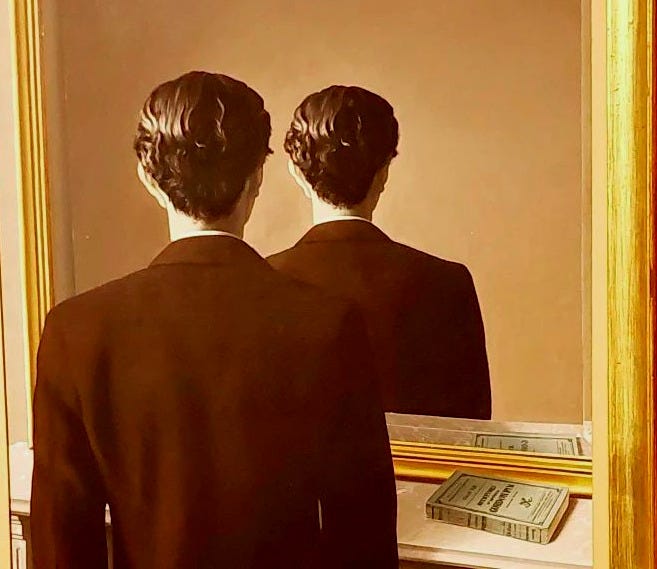

Actually, Existentialism is far more concerned with the way we do what we do, and whether we’re even aware of ourselves doing it. It’s not a popular mode of thinking for this very reason. The last thing most people want is to acknowledge themselves as Selves doing anything. Their “doing” is an aid to self-forgetfulness. The great Existentialists homed-in on our many acts of self-deception, asking what it’s all about.

The question then arises whether you are mindful when you think and act, or merely concerned with finishing up, satisfying expectations and getting someone’s approval. Are you aware of your awareness and do you observe yourself being yourself? Are you really what you imagine yourself to be, and how could you start finding out? You may be kind and good, but are you “Authentic?”

What on earth is that?

Existentialism raises this odd question and provides profound answers as to what it means to be an authentic human being. It might be more than kindness, goodness, charity, sociability, skill and intelligence.

But again, we ask, what the devil is “authenticity?” What does it mean to live authentically, and how am I to know if I am doing so? Is the matter simply not worth bothering about?

The concepts of authenticity and inauthenticity are arguably the most complex and least understood notions in “Being and Time” – Havi Carel

Actually, we don’t normally encounter people who are that crazy about it. When is the last time you spoke to someone sincerely worried about whether their life had “meaning” or not? It’s not a stretch to say that without the philosophy of Existentialism, the world wouldn’t know or care about the subject. Even the rich and famous wouldn’t change their spendthrift lifestyles, and the lower classes wouldn’t stop trying to be like them.

With this in mind, Existentialists inquire into that which few notice or care about – a human being’s actual experience in the world. What do we really know about it? What answer do we get when we ask people to describe their existence? Can we do as much without getting stumped, puzzled and unintelligible? How do we experience the world? Have we ever been astonished that there is something rather than nothing? And what about the “self” doing the experiencing? What do we know about it in substantial terms? Who says whether a self’s experiences have “meaning” or not? Who deigns to call another person authentic or inauthentic?

The answer is that authenticity is not a matter commented on by others. It’s not a matter of public opinion. It’s not necessarily on display. It’s one’s own business, which makes Existentialism very personalistic.

Heidegger's ethics of authenticity deals first and foremost with oneself, rather than with Dasein's responsibility to others – Havi Carel

Oh yes, and the most important point and problem: If one knew what it means to live “authentically,” would they gratefully choose it or instead run headlong in the other direction? Authenticity and uniqueness may be utterly repugnant to those happily embedded as non-selves within the ‘’norm.’’ What’s the reason?

It has been noted that we humans are strange, contradictory and often sorry creatures. Nevertheless, comment on ourselves is possible because we are, in an apparently non-conscious universe, self-reflexive thinking beings.

The term “human being” implies intelligent mechanism. Human is flesh, bone, hide and hair, fibre, marrow, blood, tissue and little grey cells. But the odd term “Being” connotes what exactly? We are bound to stop and think about it. The word trips us up. It’s obscure and opaque. Maybe it’s similar to Homo Sapiens, the thinking, intelligent, wilful species on the planet. Plato, Aristotle, and a good many other leading philosophers throughout history presumed it to be so, and it’s still the dominant view.

As the thinking species we do indeed stand out as unique, yet how many humans give their “transcendence” the consideration it deserves? How many give thinking the thought it deserves? Not too many it seems. Even among those who do think about thought, how many contemplate how self-reflexivity is possible? How many ask whether the answers provided by science hit the mark? Do scientists explain mysteries or are they more inclined to explain them away? What if science’s explanations for reality are misleading and wrongheaded? Where do we go and what do we do if the answer is yes? As said, Heidegger wasn’t convinced that science, religion and philosophy had legitimate futures.

…philosophy has not been up to the matter of thinking and has thus become a history of mere decline – Martin Heidegger

Science is allegedly built on objective observation. Well, that doesn’t seem right for a start. After all, how do I get out of my head to “objectively” experience the world appearing before me? Is what I know about the world to be trusted? Does my mind really give me direct access to the way things are, or is it all a matter of appearances and representations? If the latter is the case, what about my self-image? Is it also merely a matter of mind-contrived appearance and representation?

…the objective, as such, always and essentially has its existence in the consciousness of a subject – Arthur Schopenhauer

Additionally, why is everything we know about mind by way of mind? How does a singular mind split itself into subject and object? Is the capacity learned from the world, from our experiences with entities and objects around us, or is it an innate capacity? If my mind didn’t have this polarizing ability, could I be aware of a world? Could I be aware of myself as an individualized self within it? How am I able to form thoughts and questions like this? Why does being and existence matter to me?

Certainly, we agree that this mental reflexivity separates us from animals and inanimate objects. A wall isn’t concerned with its future. The carpet doesn’t cry if it is removed and thrown into a dumpster. The sofa does express sorrow if it is taken away from the chairs and tables and placed in another room. When clouds dissipate, they do so without cries of regret. Cut grass grows back again and again without complaint. Millions of cells in our bodies silently die every day without going on strike. Only humans are concerned and caring, especially about themselves. Only humans wonder whether their lives have “meaning.”

No object or animal is concerned with its eventual demise. Animals have memories alright, but don’t dwell on the past. They do not worry about or plan for their futures. They are victims of immediate desire and are wholly satisfied when these are met. They do not introspect and fret over their public image, life-purpose or past failures. They have no ambitions and don’t ask whether their existence is “meaningful.” If one sheep in a field dies the others don’t display black armbands. They just continue grazing as if nothing happened.

To be a thinking being means we possess a will, and a free one at that. We are free to change our minds and lifestyles in a multiplicity of ways, in a heartbeat and for any reason. It’s not easy to tell whether it is our will that direct our thoughts and desires, or whether our thoughts and desires direct the will. It’s also not too easy determining whether we are motivated by the raw Nietzschean Will-to-Power or more sophisticated Will-to-Meaning. Nevertheless, we can all testify to feeling underwhelmed once our desires are met. Do we ask why this is? Not really. We’re too busy getting caught up with new desires and envisioning the future in which we hope to realize them. The future matters a lot to Existentialists, as we’ll see.