…one might easily come to the idea that the most extreme sharpness and depth of thinking (Denken) belongs to the mystic. This is moreover the truth. Meister Eckhart testifies to it – Martin Heidegger

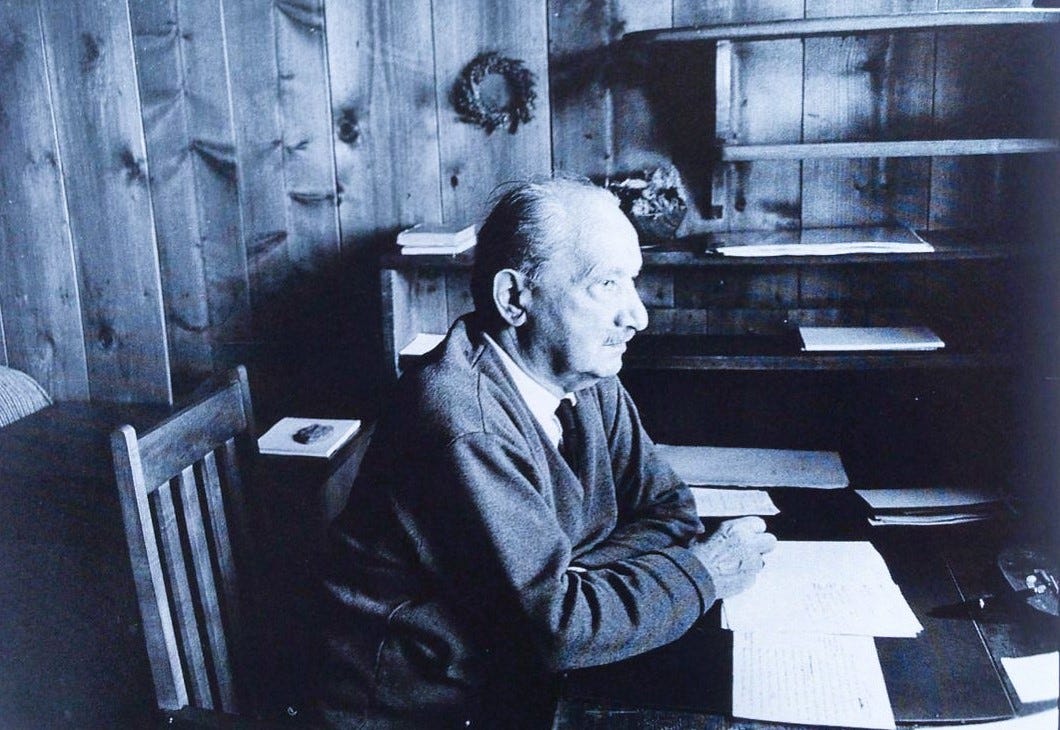

It is now possible and necessary to consider the question of Heidegger’s mystical leanings and delve into the pros and cons of the issue. Let us not heed the static of academic goons who ad nauseum repeat the tired party line that he wasn’t “a mystic,” offering not a jot of substantiation for their myopic assurances. They imagine that they’re mere statements will be blindly accepted worldwide, such is their outright duplicity and arrogance. Ignore the obligatory naysaying of the institutionalized and we recognize at once the mystical quality of Heidegger’s later thought.

It helps if we widen our definition of the term “mysticism,” making sure we are not influenced by religious connotations. Let us think of it in terms of Mystical Naturalism and Mystical Aestheticism, as we find with the work of Holderlin, Goethe, Schiller, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Emerson, Pater, Rilke, Marcel and Barfield, etc.

This is not to endorse Pantheism of any kind, since we are not tracking the activity and presence of a religious god, nor are we considering any form of Christian or Eastern esoterism.

We can appreciate the mystical within Heidegger by referring to early German thinkers such as Meister Eckhart, Jacob Bohme, Angelus Silesius, and others. Certainly, in his later works we find direct allusions to early German mystics such as Eckhart and Silesius. Several terms and ideas in Heidegger’s later works – particularly Sway and Releasement – resemble the thought of Duns Scotus and Gerard Manley Hopkins.

His ruminations about the majesty of the natural world, his evocative musings on forest walks and half-lit landscapes are reminiscent of Emerson, Coleridge, Wordsworth, and of many German Romantics. It is known that he lectured on Schelling’s Naturophilosopie, and his love of and debt to Rilke and Holderlin has also been widely acknowledged.

His repeated use of terminology right out of the antique German mystical tradition caused much consternation. Materialistically minded readers reacted in horror, accusing him of obscurantism and incoherence.

Heidegger subsequently traded the idealism of fundamental ontology for the mystical posture of his later works…which no longer assert the dependence of being on human being, but instead treat being as something essentially mysterious and inexplicable – Taylor Carman

Heidegger’s evocative statements about the ambivalent qualities of Being strike the reader as particularly non-materialistic and mystical in tone. His emphasis on Being’s concealment is akin to the thought of the high German mystics of previous ages. His comments about moods, preconscious states of awareness, and of letting-be, etc, are akin to Taoist teachings. It is also striking that he worked on his own translation of the seminal mystical book, the Tao Te Ching by the ancient Chinese mystic Lao Tzu. Senior Taoist thinkers from Japan invited him to live and teach in Kyoto, and he invited top Taoists to visit him for extended periods in Germany. The most eminent Taoists thinkers of the Kyoto school openly declared Heidegger’s thought to be essential for an understanding of the deepest Zen and Taoist principles.

His statements about “mystery,” “silence,” “care,” “dwelling,” “letting-be,” “gifting,” “gratitude” and “meditative thinking,” etc, can be identified as mystical, as can his comments about the grand humility of authentic types whose perspectives on existence are vastly more attuned and sensitized to reality than that of folks entangled in ontic life. Indeed, his description of the authentic person – especially in the guise of the loner and outsider – can be regarded as semi-mystical.

Clearly, Heidegger’s descriptions, in this regard, influenced great Existentialist writers such as Herman Hesse, Gabriel Marcel and Albert Camus. Some point to his focus on Being-Toward-Death, finitude, angst, evasion, self-deception, collectivism, inauthenticity, nothingness, the importance of art, etc, as quasi-mystical elements of his overall philosophy.

The meditative man is to experience the untrembling heart of unconcealment. What does the phrase of the untrembling heart of unconcealment mean? It means unconcealment itself in what is most its own, it means the place of stillness which gathers in itself what grants unconcealment to begin with – Martin Heidegger

Some Heideggerian scholars, such as William Barrett, John Caputo, Richard Capobianco, Alfred Denker and Barbara Dalle Pezze are open to the idea that Heidegger’s work is of a mystical bent. Others think of it as semi-mystical, rightly advising that Heidegger’s mysticism is not automatically to be associated with better known mystical schools, Christian, Gnostic, Sufi, Vedic, Chinese, German, Romantic, or other.

An “esoteric” reading of Heidegger’s texts convinces me that he can correctly be defined as a Mystical Naturalist, or in modern parlance a Naturalistic Pantheist or Religious Naturalist. It is for this reason that thinkers such as Arne Naess formed the Deep Ecology movement, largely due to Heidegger’s ideas on the importance of nature and man’s pathological insensitivity toward it.